on the road trip

each billboard is the same –

her smiling face

on the road trip

each billboard is the same –

her smiling face

As a postscript to my recent post on movie actor and paperback author Lynton Wright Bent, my attention has been drawn to something that puts elements of the bibliography in some doubt.

There’s no copyright on names – I share one with the former drummer of Roxy Music, for example, and there’s an academic web site that keeps telling me I’ve been quoted in innumerable articles – and I’m well aware that The Hectic Headspace of Abigail Squall (2018) was not written by the same Scott O’Neill. So I wasn’t surprised when someone came up with information to suggest that at least one of the titles in the bibliography may not be by Lynton Wright Brent at all.

Martian Sexpot (Jade, 1963), according to The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, was authored by Peggy O’Neill Scott Fields. She and her husband Lynwood Paul Fields wrote together, as Barton Werper, and produced a notorious series of Tarzan novels, which were taken out of circulation when the estate of Edgar Rice Burroughs sued the publisher.

If Martian Sexpot is now in doubt, then Profile of a Pervert (Jade, 1963) must be also. What does that say about the Gold Star titles? Well, difficult to say at this point, but I’m keeping the case file open…

In 1936 a quirky little book was published, entitled Gittin’ in the Movies. It was written in a kind of American “country” eye-dialect, and was a tongue-in-cheek volume on how to inveigle your way into appearing in films. Its author was Lynton Wright Brent, who was then six years into a twenty-year career in which he appeared in at least two-hundred-and-forty movies. Never a star as such, he was often to be seen in a check shirt and a Stetson in the role of a henchman, or as one of the irate townsfolk about to lynch the wrong man, or as a gang member, or as a fall guy for the Three Stooges.

Brent was born in Chicago in 1897, and died aged eighty-three in Los Angeles in 1981. He was the son of William Lynton Brent, who founded and developed the Los Angeles suburb of Brentwood. As well as being a movie actor he was a painter – more as a leisure activity than as a serious artist – and an aspiring author. The next book of his I could find, after Gittin’ in the Movies, is a novel called The Bird Cage, published in 1945 by Dorrance & Co. It is about the Bird Cage Theatre in Tombstone Arizona in the 1880s. I have a press clipping from a Tucson newspaper I can’t identify (possibly the Tucson Daily Citizen) which refers to The Bird Cage as Brent’s “first novel,” and refers to another of his “historical novels of Arizona” being scheduled for publication in 1946. The clipping states that this second novel was about life in the town of Bisbee in the same era, but if it was ever published I can find no reference to it anywhere. The clipping also states that Brent was heading back to Hollywood to sell the movie rights to The Bird Cage, but again that is another cold trail. Perhaps the release of John Ford’s landmark My Darling Clementine in 1946 put the cap on movies set in Tombstone for some time.

You may be wondering how I found out about Lynton Wright Brent, and what started me on his trail.

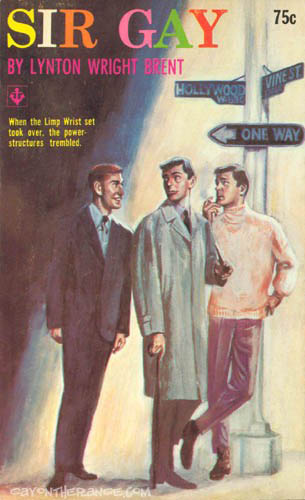

“Hello. I don’t know what this is, but I want to read it,” was the pm I got on social media from a friend a few days ago. Along with the message came a picture of the cover from the mass-market paperback Sir Gay.

After a couple of clicks of the mouse, I found what I was looking for, and messaged back “It’ll cost you at least £145!”

As we conversed about this piece of mass-market ephemera, I busied myself looking for more. The author’s name rang a bell, and I recalled that Brent had written a couple of novels that fell within my sphere of research – Lesbian Gang (1964) and Lavender Love Rumble (1965). Of my two standard reference books about paperbacks, one didn’t mention the publisher “Brentwood” at all, and the other had one entry for them, and that was a fourth title. As I searched the internet, more titles were beginning to emerge; I boasted that, given half an hour, I could come up with a complete bibliography for Brent, at which my friend showed some sceptical amusement.

So, how did I get on? Well I discovered that a good decade on from the end of Brent’s movie career, and almost twenty years since The Bird Cage, he became a latecomer in the world of cheap paperback sleaze, publishing a slew of novels at what seemed a single go. Many of them were on a western theme, with added pornography, and I have a feeling that they might have started their life as a portfolio of straight westerns that failed to find a publisher. Several of these seem to have been published by “Brentwood” – I assume that Brent couldn’t find a publishing house, so he founded one! Others, purporting to be non-fiction exposés, were published under the pen-name Scott O’Neill. The promised bibliography follows. I hope you enjoy it. Information on “pulp” authors is often quite meagre, so I am prepared to bet that there may be unknown Brent oeuvres out there, maybe under other pen-names. If you know of any, let me know!

Lynton Wright Brent – bibliography

Including titles by Scott O’Neill*

Novels etc.:

Apache Killers – Powell, 1969

Apache Massacre – Powell, 1969

Apache Tomahawk – Powell, 1969

The Bird Cage – Dorrance & Co, 1945

Blood in the Street – Powell, 1968 (with Richard Fusilier)

Campus Call Girl – Gold Star, 1964*

Daughter of Bonnie & Clyde – Producer Books, 1971 [apparently the novelisation of a Norman Hudis screenplay, but no such film seems to exist.]

Death of a Detective – Powell, 1969

The Desert is a Woman – Brentwood, 1965

Detective on the Prowl – Powell [possibly as Scott O’Neill]

Flaming Lust – Brentwood, 1964

Gittin’ in the Movies – Moderncraft, 1936

Hollywood Crime and Scandal – Powell, 1969

Lavender Love Rumble – Brentwood, 1964

Lesbian Gang – Carousel, 1964

Lust Gallops into the Desert – Brentwood, 1965

Martian Sexpot – Jade, 1963*

A New Look at the Lesbian – Nite-Time, 1963*

One Man’s Crime – Powell, 1969

Outlaw Village – Powell, 1968

The Passion Tree – Brentwood, 1965

Passionate Peril at Fort Tomahawk – Brentwood, 1965

Profile of a Pervert – Jade, 1963*

Sex and the Alcoholic – Gold Star, 1965*

Sex and the Divorcee – Gold Star, 1965*

Sex and the Hospital – Hemisphere, 1965*

Sex and the Jet Set – Gold Star, 1964 *

Sex and the Starlets – Gold Star, 1964*

The Sex Demon of Jangal – Brentwood

Sex in the Service – Gold Star, 1965*

Silent Sex Trail – Brentwood, 1965

Sir Gay – Brentwood, 1965 [$180]

Squaw Trail – Brentwood, 1965 [Anchor]

The Sundown Kid – Powell, 1969

Violent Love Stalks The Plains – Brentwood, 1965

Warpaint in the Desert – Powell, 1969

Stories:

“From Mexico I Came” – Script, August 1940

“The Marshal Wears a Mask” – Western Aces, June 1943

“The Texas Kid” – credited as the story behind a Jess Bowers screenplay.

“The Sheriff Lends a Hand” – Masked Rider Western, March 1943

“Der Sex-Trail” – Lady Derringer No.6, 1994 [65-page periodical by various authors, published in German by Martin Kelter. The story may be a posthumous reworking of Brent’s novel Silent Sex Trail]

__________

I acknowledge the web site b-westerns.com for much of the above information.

Up to now I have used this alphabetical series to look at visual art. This time I am going to focus on a musical piece. In her 2017 TV series Tunes for Tyrants: Music and Power, Suzy Klein has this to say about Carl Orff’s famous Carmina Burana:

There’s one piece written in the 1930s that I think more than any other captures the toxic spirit of the age. Carmina Burana by Carl Orff stirs us up to feel tense excitement with its violent power. Its hypnotic rhythms chimed brilliantly with the frenetic atmosphere of Nazi Germany, where it swept the crowds off their feet. The Nazi party newspaper called it “The kind of clear, stormy, and yet disciplined music our time requires.” Carmina Burana has become one of the most performed pieces of classical pieces, a staple of popular culture, used by film, TV, and advertising, a cliché of macho, apocalyptic glory. The music has long outlived the politics of the time. But is there something inherently fascist about the bombastic, unreflective emotion written into its very notes? We might like to think that the music we still love today has nothing to do with the dark and distant politics of a terrible time, but I’m not sure it’s quite that simple. I suppose if listening to music can’t make you a better, more moral person, nor can it by the same token make you an immoral person. That said, Carmina Burana, for me, is the ultimate piece of empty music. A load of sound and fury signifying nothing. It pushes our buttons and it tries to provoke our basest emotions. I cannot help but hear the hate-filled ideology it grew out of when I hear those notes. And our willingness today to still submit to its power carries with it, I think, a health warning, that when we embrace music like this, we also have to recognise that it came out of a profoundly evil regime.

Klein’s commentary is seasoned with “I think” and “for me” and is therefore very subjective, and indeed emotional rather than intellectual, but she misses several important points in her assessment. Firstly, that Orff’s relationship with the Nazis was an ambiguous one. He was not a party member, he was one of the countless thousands (millions?) of Germans who timidly got on with life and survived under the regime. That might have been cowardly, but Klein herself acknowledges elsewhere in her series that so many artists – and ordinary people – did just that. He took commissions that did not do him honour, such as submitting a new score for A Midsummer Night’s Dream to replace Felix Mendelssohn’s. The ambiguity of Orff’s relationship with the regime does not, of course, free him from its taint. However, it does make it legitimate to look at his work and ask whether it did in fact “grow out of” a hate-filled ideology and a profoundly evil regime simply because it was composed in it. There is sufficient evidence to say that it did not.

Klein’s reaction is to one part of Carmina Burana only – the dramatic, primary-coloured ‘O Fortuna’ that brackets the whole. The work is composed of settings of twenty-four medieval poems, of which ‘O Fortuna’ is only one. None of the other poems is given such a setting. What ‘O Fortuna’ does is grab our attention and demand that we listen to what is going to come after. Klein’s attention is fixed solely on one twenty-fourth of the whole.

But even if we look at ‘O Fortuna’ on its own, it can’t be judged as Nazi propaganda. The words, as with the other poems, are profoundly subversive to Nazi ideology. The poems were composed by thirteenth-century Goliards, disaffected young student clergy who, from within the monolith of medieval Christianity, wrote secular and satirical verse. In monolithic 1930s Germany, clothed within their original Latin, the words of ‘O Fortuna’ may seem neutral. But consider how they would have been heard if translated into German. Orff titles this piece ‘Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi’, which we could render as ‘Fate Empress of the World’. The words “Imperatrix Mundi” are not to be found in the original, they are Orff’s. When you consider that one possible translation into German of the word “imperatrix” is “Führerin,” you see a challenge emerging. Hitlerism was an ideology that privileged the notion of “will,” specifically the will of the Führer, as the governing force of historical change. Fate, on the other hand, “strikes down the strong” and, by inference, carries away the empire-builder and the visionary. ‘O Fortuna’ is a clarion counter-manifestation to Nazism.

Before it was ever called clear, stormy, and disciplined by someone writing for the Nazi party newspaper – someone who also had clearly only listened to the opening section, and moreover was only semi-literate in Latin – Carmina Burana was heavily criticised for being “un-German” and “pornographic.”[*] How it managed to gain official favour is testament to the whims, unreliability, and ultimate stupidity of Nazi artistic criticism.

It is possible that Orff slipped one past the Nazis. I ask why, when an earlier contributor to Suzy Klein’s series had been able to see Shostakovich as – perhaps – secretly slapping Stalin’s face, Klein herself could not see the possibility that Orff was secretly slapping Hitler’s.

You know, I know, and Suzy Klein knows, that any oppressive regime is facilitated not by its handful of fanatics and enforcers, but by its millions of ordinary people who keep their heads down and get on with their lives. She makes a similar point herself, elsewhere in the series, to the effect that people will act to ensure the safety of their families and themselves. Such people are shopkeepers, civil servants, postal delivery people, midwives, street-sweepers, carpenters, electricians, nurses, doctors, you, and I. Some of them occupy positions that are more prominent, say in art or music, and when their names live on it seems that the compromises they have had to make in order to survive are amplified above the ordinary. But they are not amplified. They are exactly of the same order as the compromises that we would all have made.

Klein seems to distrust the emotionalism of Carmina Burana. But you can’t really march to it the way you might be able to march to Die Fahne Hoch. Its relentless rhythm is not the tread of jackboots, it is the musical embodiment of fate, it is the steady rattle of the wheel of fortune. Emotion is a legitimate component of the artist’s toolbox, to be applied lightly with a fine brush or heavily with a bricklayer’s trowel. Even if Orff’s intention was to overwhelm us with his opening to Carmina Burana, the emotions evoked express his own fascination with a historical, intellectual disaffection with the monolithic. Let me put this personally: I could not relate at all to Orff if I had not detected immediately a huge amount of sheer effrontery in this music.

I will offer an obvious caveat. My regular readers know my long-time interest in W.G. Sebald, and in his great concern that Germany’s Nazi past had been whitewashed and its Jewish component forgotten. In pointing out flaws in Suzy Klein’s reasoning I do not intend to whitewash Orff. Denazification labelled him as grey, and grey he remains. I thoroughly enjoyed Klein’s series, and commend it. However, let me end with another quote from 2017, this time from one of Hilary Mantel’s Reith Lectures: “For a person who seeks safety and authority, history is the wrong place to look. Any worthwhile history is in a constant state of self-questioning […]”[**]

[*]Unsigned text, http://www.emmaus.de/ingos_texte/carmina.html

[**] Hilary Mantel. “The Day is for the Living.” BBC Reith Lectures, 13th June 2017. bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/b08tcbrp

I was recently sent a screencap of a conversation on social media. The point at issue was a writer’s choice of words when describing Australian Aboriginal peoples, amongst others. The writer stated that even if it were possible to return to the “innocence” of the Aborigine, we would, from that point, inevitably begin to re-complicate our life with technology, in order to deal with our environment.

Why? After all, the Aborigines haven’t. The problem lies entirely with our assumption that the way the North-West quartile of the world developed – basically the European nation-states in intense competition from the 15c onward – is some kind of default. Our arrogance in assuming this, and from there piling non-sequitur upon non-sequitur, is expressed in our assuming that the Aborigines’ life is one of “innocence” and totally missing that it is highly sophisticated. Just totally differently from our own brand of “sophistication.” A culture based on fitting into a complicated and dynamic environment puts wisdom before technology, needing nothing more than a woomera to add force to a hunting spear, or a boomerang to scythe into a flock of rising birds. A culture that puts technology before wisdom, well… we’re living in it, and it’s a nightmare.

In an earlier post I mentioned a lightning sketch that the German expressionist Kirchner did of one of the Benin bronze plaques appropriated by a late 19c punitive expedition by a British military force. The assumption normally made in comparing two such works of art is that the European artist has taken the non-European as an example of primitive vigour and is trying to inject an element of that into the staid, conventionally representational artistic culture of Europe. As it happens, I challenged that assumption about Kirchner, but the general point remains about such drawing of inspiration by European artists from non-European art. The sudden intrusion of distorted “African” masks into Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is often cited, more accurately, as an example of this “primitivism.” Quotation marks here are deliberate, because they emphasise the arrogance of assuming an amorphous Africa and a pool of similarly unsophisticated, almost interchangeable cultures.

What has this to do with Sam Nhlengethwa’s It Left him Cold?

This work of art, executed in 1990, is dark and abrasive. Its use of collage distorts proportion and perspective. Is it even “art” – the perpetual question of this web site is what the hell that is anyway – or is it more a political statement? It’s subject matter is the murder in custody of Steve Biko in 1977, and it expresses the ugliness of the oppression that brought about that atrocity.

Do I even have the right to analyse it as art?

In 2020, in a world in crisis, the Black Lives Matter movement speaks. We have no right to “let” it speak, we have no right to “legitimise” it. Its right to speak and its legitimacy are not in our gift. Similarly, Sam Nhlengethwa doesn’t need our permission to put It Left him Cold into view.

That might be what I’m thinking as I gaze out of my window. This still shot was made during two days’ intensive filming, on location at and around my house, for a short film, working title ISS_Overs. It is being made by Diogenes Films, under the direction of Luka Vukos, and it concerns the solitude of one person during Covid-19 lockdown while the International Space Station hurtles overhead. I’m looking forward to its eventual release…