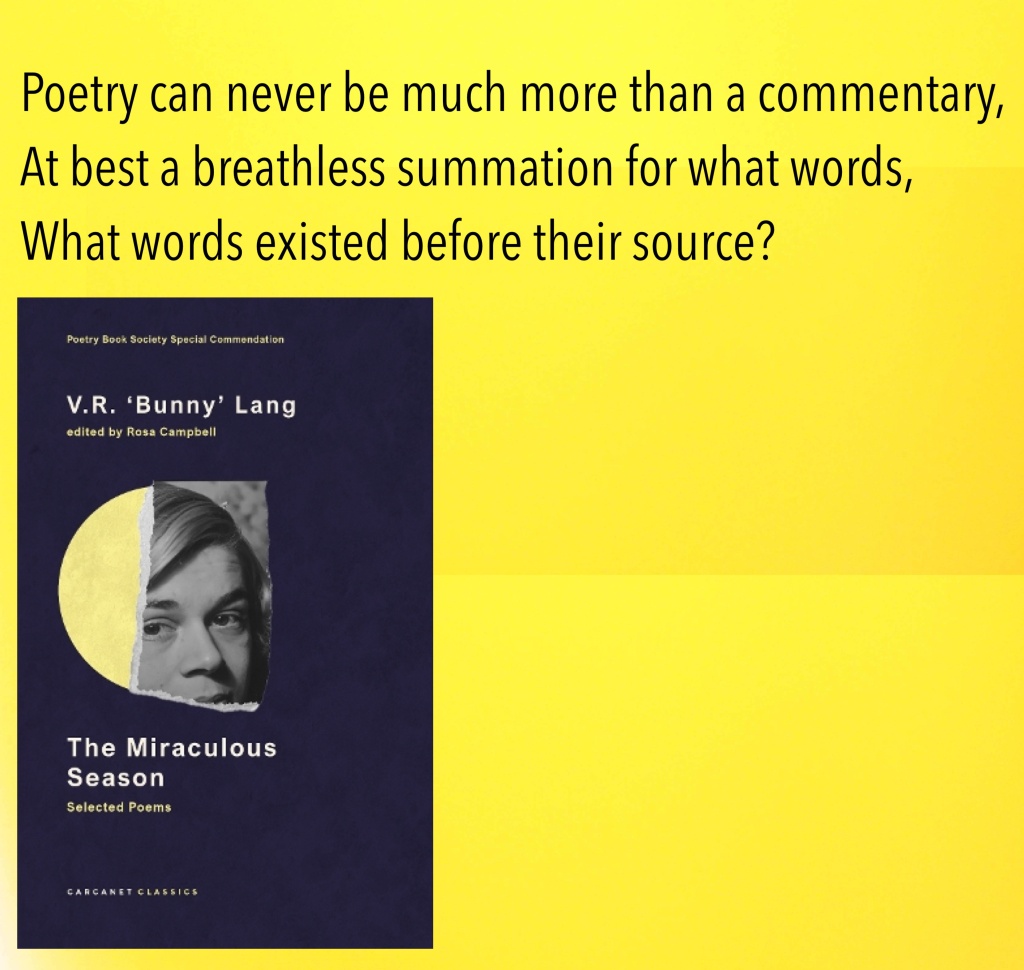

The Miraculous Season: Selected Poems. V.R. “Bunny” Lang. ed. Rosa Campbell. Carcanet Classics, 2024. pp.232. ISBN 978-1-80017-337-8.

If Bunny Lang is mentioned in the same breath as any other poet, it is usually Frank O’Hara. Given that, as editor Rosa Campbell reminds us, Lang and O’Hara worked out together how to be poets, if you approach this book looking for echoes of O’Hara’s “I did this, then I did that, then I did something else” poems you will be bewildered. That isn’t how Lang works. If I can compare her to anyone, then I haven’t been struck so forcefully by poetry since reading Lyn Hejinian. The placement of text, spaces, upper-case letters, and so on in poems like “Pique-Dame” or “I Waited Five Hundred Centuries for the White Crow” makes me think instantly of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Poetry. But whereas Hejinian makes it clear that she loosens her own proprietorship of a poem, thereby relinquishing her authority over meaning into the hands of her readers, Lang serves us with poetry that seems so intensely personal that we feel she would rap our knuckles if we tried any such malarkey with her words. She seems to pose to us the questions “What does poetry do? What is it for?” and as soon as we start to answer she interrupts us and says “No. You’re wrong. Stop and think again.” And then, on the other hand, her poems seem to grow without any such deliberation.

Her poems are difficult. Not long (well, not many of them), not full of obscure words, apparently not deeply philosophical, not high-flown, just difficult. But only difficult inasmuch as where she starts a poem doesn’t necessarily indicate where she’s going with it, nor that stops on the journey and the terminus will be recognisable. That is what holds me, though it sometimes leaves me begging for a connection that isn’t obviously there; it is as though the difficulty doesn’t make any poem inaccessible. Read a poem – wow! – on to the next one, and the next, and worry about meaning some other time, is one way to approach them; no one will penalise you if you want to sit and puzzle, and puzzle and sit, and seek and wonder, though.

Rosa Campbell spent a long time poring through the archive of the documents of Lang’s life in the Houghton Library at Harvard, unearthing the collection in this book. Some of them have been published before, many have not. Campbell writes, of the things she felt she had to leave out, that they are “fragments […] handwritten in pencil on little blue sheets and scribbled in the margins of theatre programmes, typed on the torn-off top of a letter draft or hovering uncertainly at the bottom of the manuscript of a poem.” Oh how I wish they had been included! Or that they had been given an edited volume of their own – the koan and haiku of Bunny Lang! Or perhaps I will take my own copy of The Miraculous Season over to Harvard, seek out these fragments, and use my pencil to make a palimpsest around and through the printed verses!

These fragments may be part of the chronicling of the creation and interruption of Lang’s poems that Campbell draws to our attention, the “typewriter which jams” and the “voice downstairs” and the “telephone which enters” and every damned porlocking thing that dams the sacred river of Lang’s poetsmithy. But sometimes the metal of a poem is left with only a coat of primer, declared finished by circumstance. We sometimes look at work with the raw materials deliberately left visible, the scaffolding left in place as part of the project.

I’m at my first reading. It won’t be my last. How could it be. I am picking up lines like “Now guests no longer come here to dismay our waiting” (and I remember Michael Flanders’ quip, noting that the Greek word for “stranger” and “guest” are the same, “Hence ‘xenophobia’ – fear or loathing of guests”). “The workaday webs of us admiring spiders.” “[…] folds and faults / Zones and vaults.”

I learned something, though. There is no end to the week.

Sunday you can call it but it does not mean

That Sunday anything will end. No indeed.

“Stones see back” (Hello Maurice Merleau-Ponty and your principle of reversibility!). The whole of “Things I Have Learned In Canada,” reading like five verses from a cock-eyed apocrypha, proverbs, handy hints and tips, lackadaisical matchbox aphorisms designed to cause more trouble than cure, some bloody brilliant such as “Use your ears and you will be able to speak a variety of languages. Speak them and forget your own.” Yeah, maybe start with Ojibwe? A love poem (?) that ends:

Terror and weakness, Marvellous James

With nothing on his face but purpose

And sometimes, ownership.

January, Betelgeuse –

Brazil, tundra, stars,

I love you very much,

I recognise my loss

I love you very much,

I love you very much.

A suicide note containing a horrible curse – “I wish you no petty dismays.” A surprise party where the bridegroom doesn’t recognise the guests. A whole poem:

At last the Indians have their summer.

While the rest of us were at the beach

They were waiting.

A letter from a Grandma that begins with “And.” If you have “passed unharmed through the miraculous season” you will have reached the end of the book. You may want to start again. I know I want to.

Let me leave you with a thought about the poem “Two Cats Have Killed A Bird.” It is clearly inscribed “For Frank O’Hara” and is as near a love-song one to the other as we’re likely to get, even though as a love-song it is the sort that you need to be dreaming to recognise for one. Of Lang’s juxtaposition with O’Hara, Campbell says, “This is often the fate of women who happen to be connected to famous male artists and writers, regardless of their own professions or talents; relegated to the status of auxiliary, passive inspiration, they freeze into silence.” That alone would be sufficient for this book to be both valid and valuable. The fact that Lang is capable of elbowing any (male) member of the New York School aside to wince and count his ribs, adds to the validity and value a poetic power.

The Miraculous Season was a labour of love on the part of Rosa Campbell, is evidence of her academic tenacity and, in showcasing V.R. “Bunny” Lang, showcases one hell of a 20c poet.

__________

::::

::::

::::

::::

::::

Any adverts that appear on this page are a result of the platform and do not imply an endorsement by me.